How it begins ...

Prologue (Winter 1268)

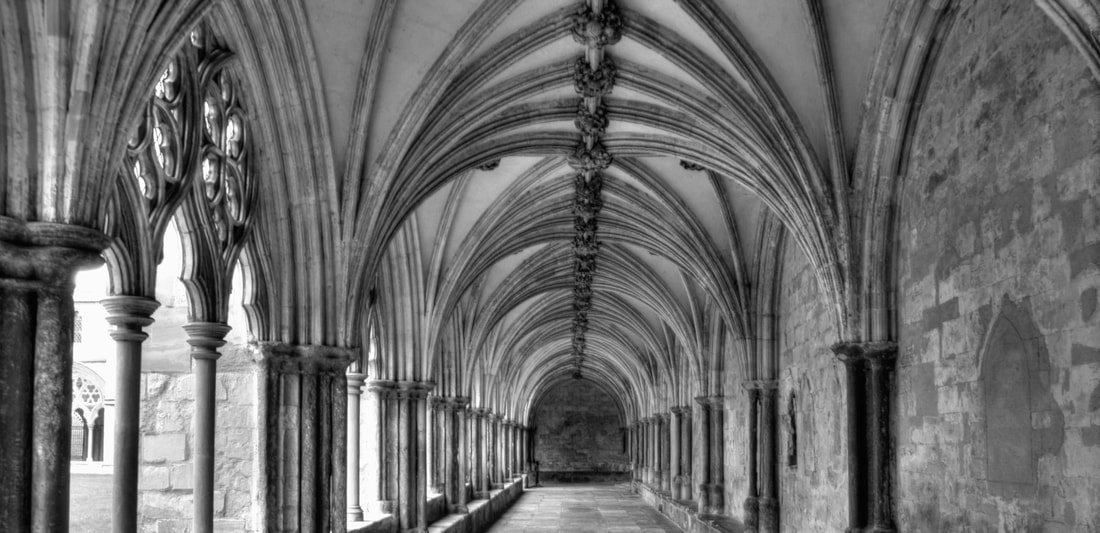

The hooded figure made slow progress through the thickly piled snow that covered the ground, turning the Abbey grounds into a winter landscape the like of which the monk had not seen for many years. His dark woollen monk's robes were soddened and heavy and his feet made deep impressions in the glistening snow. Under his arm he carried the small iron-bound wooden chest, locked and sealed by him in the church. The box seemed to become heavier with each step, far heavier than it should for its size. He struggled through a wide archway and into a broad courtyard. Hardly any sound accompanied his progress other than the crunch of the snow underfoot and the beating of his heart, pounding in his ears. Around him the stone walls of the Abbey buildings glowed white in the pale moonlight. Behind him the vast tower of the Abbey church cast a long shadow. Suddenly the sound of beating wings and the whisper of air made his blood run cold. He stumbled, almost dropping the chest as the ghostly white shape flew towards him. His breath came out in jagged bursts as he realised that the shape was just a barn owl, the snow having driven him from the surrounding fields to look for prey. Sensing him, it veered away, flying high over the archway behind him.

Pulling himself together, the man moved forward, then hesitated as he stepped out of the moonlight into the heavy darkness thrown by the tall buildings and a shudder ran down his spine as he felt the light in his soul flicker and almost fail with every step.

Brother Anselm muttered a quick prayer, although he was not sure anyone was listening in these strange times. His fear of the darkness was nothing compared to the horror of the past forty-eight hours and if he could survive that, he could survive anything. He came to a halt. The small wooden door facing him was very narrow and hardly tall enough for a man to pass through without bending. For a brief moment, Brother Anselm allowed himself a smile as he thought of the Abbey cook, Brother William, whose ample frame could certainly not pass through this door.

Brother Anselm searched among the folds of his robe for his pocket, pulled out a large black iron key and inserted it into the lock in the door. He hoped that the precious oil he had used earlier in the day would, by now, have now eased the rusty mechanism. The chapel, one of the oldest buildings in the Abbey complex was hardly ever used; its limited space made it redundant now for anything but a storeroom and the story was that the key had been lost years ago.

His mind returned to the scene in the Abbot's room. Although it had been early afternoon and the pale wintry sun was still in the sky, there had been little light in the room. The large candles fixed onto the walls made hardly any impact on the gloom. It was as if the walls themselves were absorbing the power from the candles before casting any light. There was an underlying smell of wax from the expensive candles and wood smoke from the fire as well as the sweet smell of rushes and the dried lavender scattered over the tiled floor. Anselm knew the scent of the lavender well, as he had organised the collection and drying of the herbs that now hung from the ceiling of his dispensary.

The Abbot gave Brother Anselm his instructions in a voice barely audible after the events of the previous night. He also handed him a rolled parchment, holding it between his thumb and forefinger, fearing that it was probably bewitched and not wanting any of its magic to seep into his fingers.

'This is from the Lady Alys.' The Abbot quickly wiped his hand on his robe then moved over to a large wooden and iron trunk in the corner of the room. He pulled out three keys from his pocket and inserted each one into the corresponding lock. He removed most of the contents and eventually, with a brief grunt of success, brought out a linen-wrapped object that he placed on the desk in front of the exhausted monk.

‘This key will open the small chapel door.’ He handed the parcel to the monk, folding the young man’s hands over the worn and aged linen wrappings. He whispered a short prayer. Brother Anselm turned and picked up a small chest sitting on the edge of the desk and walked slowly towards the chamber door.

‘Brother Anselm?’ The Abbot, having sat down behind his desk, rested his elbows on the desk and wearily leaned forwards. Brother Anselm paused, his hand on the smooth iron ring.

‘Yes, Father Abbot?’

‘Wait as long as possible but make sure you finish before midnight.’ He raised his head to look the man in the eyes.

Brother Anselm turned and held the Abbot’s gaze for a few moments.

‘Of course, Father Abbot.’

He forced his mind back to the present and his task. Fingers numb from the cold made it difficult but eventually he was able to fit the heavy key into the lock. With only a slight scratching noise, the key turned and the monk carefully pushed the door, which swung open slowly with a slight grinding noise. Despite knowing that there was no one but him out in the snow, he looked around anxiously. As he stepped through the door, his eyes, adjusting to the dark, made out a smooth flagstone floor. Once inside, he closed and locked the door behind him, plunging the room into total blackness. Following the instructions given by the Abbot, he moved blindly to the opposite wall of the tiny room and drew aside a thick curtain that covered a small window. A sliver of moonlight fell onto the floor of the room allowing Brother Anselm to see that it was well furnished with large silver candlesticks holding thick pale yellow candles, a pair of carved chairs and a richly decorated rug. These were rare items. The only other place where he had seen such fine furnishings was in the Abbot's house - furnishings that were in stark contrast to the monks' cell-like quarters. Brother Anselm shook his head at these observations and looking down at the box in his arms, forced his thoughts back to his task.

His eyes narrowed against the pale light as he searched for the smaller wall-hanging that the Abbot had described. He turned around and the light caught the rich embroidery of a tapestry hanging from the wall behind him. There were no other wall decorations, other than sconces filled with half-burned candles. As instructed, Brother Anselm ignored the candles and pulled the tapestry aside to reveal a small wooden door. Frowning, he looked at the chest under his arm. He really did not want to let go of it but could not see how he could hold back the tapestry and insert the key. Looking around, he took one of the larger candlesticks and wedged it against the tapestry, which gave him enough room to insert the key and unlock the door. Unlike the outer door, the lock gave no resistance. He pushed the door open and stared into the black darkness within. Guided again by the words of the Abbot, he stepped inside. The door slammed shut behind him and he felt a strong urge to scream as a bitter cold and foul smelling draught rose up from whatever depths lay beyond. He took a deep breath for strength, closed his mind to whatever spirits lurked there and searched his memory for the instructions. He reached out and tried to feel his way around but he didn't want to move too far, as the Abbot had told him that this was just a landing with steep steps to one side. He kept his back to the ice-cold wall until he found the corner. He ran his hand up slowly until he found the small ledge as instructed. He found the promised lantern and, drawing a flint and steel box from under his robe, he again faced the problem of having to let go of the chest. Bending down in the pitch dark, he laid it down on the floor in between his feet, clamping them against the cold iron bindings to make sure it did not fall over or, worse, disappear down into the dark depth of the stairs. With both hands free, he tried to strike a light. Nothing. He tried again. Nothing. Despite the cold, sweat beaded on his forehead and started to drip down his face. He tried again and the flint sparked and caught the wick. Breathing a sigh of relief, Brother Anselm bent down to pick up the chest and, with that back under his arm and the lantern in his hand, he moved slowly forward to where he could see the first of a set of stone steps. He placed his foot carefully on the first step and started down. Down and down the steps went, changing from crafted stone to rough-hewn earth. The terrible cold bit into his body and turned his hands numb but he held on to the chest and the lantern.

Without any warning the steps suddenly levelled off and with his mind focussed on each downward step, he nearly stumbled and dropped the lantern. Holding up the lantern, he saw a narrow passage fading into the distance. As his eyes adjusted to the shadows, he spotted the iron wall sconces holding large fat candles, which the Abbot had told him, would appear at regular intervals along his path.

‘Light them, my son', the Abbot had told him, ‘it is vital that you return from this task. The path is hard and dark and you will need the light to get back safely.’

Again he had to put the chest down, fearing its loss every time he did so. Drawing a now squashed and broken taper from his robe, he fumbled with the door on the lantern. Eventually it opened and he was able to get the taper to light. Cupping the flame with his hand he reached up and lit the first candle. He started down the passage. He found the next candle and lit that one and the next. His feet made little sound on the beaten earth floor and only the blood pounding in his ears and the sputtering of the candles at regular intervals broke into his thoughts. He went over and over the instructions the Abbot had given him, fearful that he would forget when the time came, using the repetition as a barrier against other thoughts that were swimming around in his head.

Suddenly he felt the narrow passage widening and he stepped into a small chamber. He raised the lantern and scanned the room. There were three exits; including the one he had come through - the entrances so black that they seemed to suck the light out of his lantern. In the centre of the room there was a large stone plinth. It was white, completely smooth and on top of it there was a small iron cage. Brother Anselm could sense that the passage had been descending further and further down into the earth below the Abbey and he was now conscious of the weight of the earth above him. He had a brief flash - a vision of his brother monks sleeping peacefully above his head, unaware of either the horrific events of last night or the gravity of his mission deep under their beds.

Brother Anselm shook his head to get rid of this image before his courage failed him. He lifted the lantern again and looked at the paintings decorating the walls of the chamber - they were certainly not of a religious nature and seemed very old. An involuntary shudder ran through him but then he felt stronger as he realised the paintings reminded him of the protective chalk circle. He did not know what the symbols were or what they meant but somehow, they comforted him. And there was little comfort here.

He looked down at the chest under his arm. Was it his imagination or was it vibrating? Suddenly he felt an overwhelming desire to open the chest, to liberate what was contained within it. It was if someone had taken over his thoughts. Lady Alys had warned that this might happen but not that the voice would be quite so powerful... or so sweet. It was promising him everything anyone could possibly want - power, money, love. Money and power, thought Anselm. He coveted neither of these. He had lived at the Abbey for most of his life - he had been born in the village and educated by the monks. He pushed the thought away. But love? He knew what love was. Love was for God. On earth, love was for the babies and children brought in to his dispensary by their worried parents - and for the Abbey and his fellow monks.

But this gentle caressing voice was offering him a different kind of love - the kind of love that he saw in the face of the young men and women of the village on midsummer's eve - the kind of love that would always be denied to him. He had never mourned the lack of such love before but the voice was urging him on and, although he tried to block it out, the face of a woman materialised in his thoughts - a women so far above him, he had not, until this moment, even dared to think about in any other way than as a friend and benefactor.

Brother Anselm shook his head violently and the vision of the woman dissolved. He started reciting his Hail Mary, as he had done every day since entering the Abbey. Slowly it started to silence the dangerous soft warm voice. He circled the room, lighting the candles. He saw that, what he thought of as dark endless tunnels were, in fact, deep alcoves hewn out of the rock, the kind that decorated the outside of the Abbey gatehouse with their statues of saints. Returning to the plinth, he stood in front of it and placed the lantern on its smooth white surface. He pulled out the parchment he had been given by the Abbot. He remembered what the Abbot had said.

‘Lady Alys has told me what you need to say, and I have written it down. It makes little sense to me but she assures me that it is a powerful...’ he hesitated, clearly not wanting to use the word spell, '…incantation.’

Brother Anselm lifted up the metal cage and placed the chest underneath. There was no way he could see of fastening the cage to the stone, but he proceeded as instructed. He unrolled the parchment. Freeing his mind from the prayer that he felt had been keeping him safe, he visualised a bright white light. Taking a deep breath, he started the incantation. The language was strange; an ancient tongue which at first felt otherworldly after the beauty of his everyday Latin but which became familiar and comforting as he read on.

He finished and stood back.

Nothing.

The hooded figure made slow progress through the thickly piled snow that covered the ground, turning the Abbey grounds into a winter landscape the like of which the monk had not seen for many years. His dark woollen monk's robes were soddened and heavy and his feet made deep impressions in the glistening snow. Under his arm he carried the small iron-bound wooden chest, locked and sealed by him in the church. The box seemed to become heavier with each step, far heavier than it should for its size. He struggled through a wide archway and into a broad courtyard. Hardly any sound accompanied his progress other than the crunch of the snow underfoot and the beating of his heart, pounding in his ears. Around him the stone walls of the Abbey buildings glowed white in the pale moonlight. Behind him the vast tower of the Abbey church cast a long shadow. Suddenly the sound of beating wings and the whisper of air made his blood run cold. He stumbled, almost dropping the chest as the ghostly white shape flew towards him. His breath came out in jagged bursts as he realised that the shape was just a barn owl, the snow having driven him from the surrounding fields to look for prey. Sensing him, it veered away, flying high over the archway behind him.

Pulling himself together, the man moved forward, then hesitated as he stepped out of the moonlight into the heavy darkness thrown by the tall buildings and a shudder ran down his spine as he felt the light in his soul flicker and almost fail with every step.

Brother Anselm muttered a quick prayer, although he was not sure anyone was listening in these strange times. His fear of the darkness was nothing compared to the horror of the past forty-eight hours and if he could survive that, he could survive anything. He came to a halt. The small wooden door facing him was very narrow and hardly tall enough for a man to pass through without bending. For a brief moment, Brother Anselm allowed himself a smile as he thought of the Abbey cook, Brother William, whose ample frame could certainly not pass through this door.

Brother Anselm searched among the folds of his robe for his pocket, pulled out a large black iron key and inserted it into the lock in the door. He hoped that the precious oil he had used earlier in the day would, by now, have now eased the rusty mechanism. The chapel, one of the oldest buildings in the Abbey complex was hardly ever used; its limited space made it redundant now for anything but a storeroom and the story was that the key had been lost years ago.

His mind returned to the scene in the Abbot's room. Although it had been early afternoon and the pale wintry sun was still in the sky, there had been little light in the room. The large candles fixed onto the walls made hardly any impact on the gloom. It was as if the walls themselves were absorbing the power from the candles before casting any light. There was an underlying smell of wax from the expensive candles and wood smoke from the fire as well as the sweet smell of rushes and the dried lavender scattered over the tiled floor. Anselm knew the scent of the lavender well, as he had organised the collection and drying of the herbs that now hung from the ceiling of his dispensary.

The Abbot gave Brother Anselm his instructions in a voice barely audible after the events of the previous night. He also handed him a rolled parchment, holding it between his thumb and forefinger, fearing that it was probably bewitched and not wanting any of its magic to seep into his fingers.

'This is from the Lady Alys.' The Abbot quickly wiped his hand on his robe then moved over to a large wooden and iron trunk in the corner of the room. He pulled out three keys from his pocket and inserted each one into the corresponding lock. He removed most of the contents and eventually, with a brief grunt of success, brought out a linen-wrapped object that he placed on the desk in front of the exhausted monk.

‘This key will open the small chapel door.’ He handed the parcel to the monk, folding the young man’s hands over the worn and aged linen wrappings. He whispered a short prayer. Brother Anselm turned and picked up a small chest sitting on the edge of the desk and walked slowly towards the chamber door.

‘Brother Anselm?’ The Abbot, having sat down behind his desk, rested his elbows on the desk and wearily leaned forwards. Brother Anselm paused, his hand on the smooth iron ring.

‘Yes, Father Abbot?’

‘Wait as long as possible but make sure you finish before midnight.’ He raised his head to look the man in the eyes.

Brother Anselm turned and held the Abbot’s gaze for a few moments.

‘Of course, Father Abbot.’

He forced his mind back to the present and his task. Fingers numb from the cold made it difficult but eventually he was able to fit the heavy key into the lock. With only a slight scratching noise, the key turned and the monk carefully pushed the door, which swung open slowly with a slight grinding noise. Despite knowing that there was no one but him out in the snow, he looked around anxiously. As he stepped through the door, his eyes, adjusting to the dark, made out a smooth flagstone floor. Once inside, he closed and locked the door behind him, plunging the room into total blackness. Following the instructions given by the Abbot, he moved blindly to the opposite wall of the tiny room and drew aside a thick curtain that covered a small window. A sliver of moonlight fell onto the floor of the room allowing Brother Anselm to see that it was well furnished with large silver candlesticks holding thick pale yellow candles, a pair of carved chairs and a richly decorated rug. These were rare items. The only other place where he had seen such fine furnishings was in the Abbot's house - furnishings that were in stark contrast to the monks' cell-like quarters. Brother Anselm shook his head at these observations and looking down at the box in his arms, forced his thoughts back to his task.

His eyes narrowed against the pale light as he searched for the smaller wall-hanging that the Abbot had described. He turned around and the light caught the rich embroidery of a tapestry hanging from the wall behind him. There were no other wall decorations, other than sconces filled with half-burned candles. As instructed, Brother Anselm ignored the candles and pulled the tapestry aside to reveal a small wooden door. Frowning, he looked at the chest under his arm. He really did not want to let go of it but could not see how he could hold back the tapestry and insert the key. Looking around, he took one of the larger candlesticks and wedged it against the tapestry, which gave him enough room to insert the key and unlock the door. Unlike the outer door, the lock gave no resistance. He pushed the door open and stared into the black darkness within. Guided again by the words of the Abbot, he stepped inside. The door slammed shut behind him and he felt a strong urge to scream as a bitter cold and foul smelling draught rose up from whatever depths lay beyond. He took a deep breath for strength, closed his mind to whatever spirits lurked there and searched his memory for the instructions. He reached out and tried to feel his way around but he didn't want to move too far, as the Abbot had told him that this was just a landing with steep steps to one side. He kept his back to the ice-cold wall until he found the corner. He ran his hand up slowly until he found the small ledge as instructed. He found the promised lantern and, drawing a flint and steel box from under his robe, he again faced the problem of having to let go of the chest. Bending down in the pitch dark, he laid it down on the floor in between his feet, clamping them against the cold iron bindings to make sure it did not fall over or, worse, disappear down into the dark depth of the stairs. With both hands free, he tried to strike a light. Nothing. He tried again. Nothing. Despite the cold, sweat beaded on his forehead and started to drip down his face. He tried again and the flint sparked and caught the wick. Breathing a sigh of relief, Brother Anselm bent down to pick up the chest and, with that back under his arm and the lantern in his hand, he moved slowly forward to where he could see the first of a set of stone steps. He placed his foot carefully on the first step and started down. Down and down the steps went, changing from crafted stone to rough-hewn earth. The terrible cold bit into his body and turned his hands numb but he held on to the chest and the lantern.

Without any warning the steps suddenly levelled off and with his mind focussed on each downward step, he nearly stumbled and dropped the lantern. Holding up the lantern, he saw a narrow passage fading into the distance. As his eyes adjusted to the shadows, he spotted the iron wall sconces holding large fat candles, which the Abbot had told him, would appear at regular intervals along his path.

‘Light them, my son', the Abbot had told him, ‘it is vital that you return from this task. The path is hard and dark and you will need the light to get back safely.’

Again he had to put the chest down, fearing its loss every time he did so. Drawing a now squashed and broken taper from his robe, he fumbled with the door on the lantern. Eventually it opened and he was able to get the taper to light. Cupping the flame with his hand he reached up and lit the first candle. He started down the passage. He found the next candle and lit that one and the next. His feet made little sound on the beaten earth floor and only the blood pounding in his ears and the sputtering of the candles at regular intervals broke into his thoughts. He went over and over the instructions the Abbot had given him, fearful that he would forget when the time came, using the repetition as a barrier against other thoughts that were swimming around in his head.

Suddenly he felt the narrow passage widening and he stepped into a small chamber. He raised the lantern and scanned the room. There were three exits; including the one he had come through - the entrances so black that they seemed to suck the light out of his lantern. In the centre of the room there was a large stone plinth. It was white, completely smooth and on top of it there was a small iron cage. Brother Anselm could sense that the passage had been descending further and further down into the earth below the Abbey and he was now conscious of the weight of the earth above him. He had a brief flash - a vision of his brother monks sleeping peacefully above his head, unaware of either the horrific events of last night or the gravity of his mission deep under their beds.

Brother Anselm shook his head to get rid of this image before his courage failed him. He lifted the lantern again and looked at the paintings decorating the walls of the chamber - they were certainly not of a religious nature and seemed very old. An involuntary shudder ran through him but then he felt stronger as he realised the paintings reminded him of the protective chalk circle. He did not know what the symbols were or what they meant but somehow, they comforted him. And there was little comfort here.

He looked down at the chest under his arm. Was it his imagination or was it vibrating? Suddenly he felt an overwhelming desire to open the chest, to liberate what was contained within it. It was if someone had taken over his thoughts. Lady Alys had warned that this might happen but not that the voice would be quite so powerful... or so sweet. It was promising him everything anyone could possibly want - power, money, love. Money and power, thought Anselm. He coveted neither of these. He had lived at the Abbey for most of his life - he had been born in the village and educated by the monks. He pushed the thought away. But love? He knew what love was. Love was for God. On earth, love was for the babies and children brought in to his dispensary by their worried parents - and for the Abbey and his fellow monks.

But this gentle caressing voice was offering him a different kind of love - the kind of love that he saw in the face of the young men and women of the village on midsummer's eve - the kind of love that would always be denied to him. He had never mourned the lack of such love before but the voice was urging him on and, although he tried to block it out, the face of a woman materialised in his thoughts - a women so far above him, he had not, until this moment, even dared to think about in any other way than as a friend and benefactor.

Brother Anselm shook his head violently and the vision of the woman dissolved. He started reciting his Hail Mary, as he had done every day since entering the Abbey. Slowly it started to silence the dangerous soft warm voice. He circled the room, lighting the candles. He saw that, what he thought of as dark endless tunnels were, in fact, deep alcoves hewn out of the rock, the kind that decorated the outside of the Abbey gatehouse with their statues of saints. Returning to the plinth, he stood in front of it and placed the lantern on its smooth white surface. He pulled out the parchment he had been given by the Abbot. He remembered what the Abbot had said.

‘Lady Alys has told me what you need to say, and I have written it down. It makes little sense to me but she assures me that it is a powerful...’ he hesitated, clearly not wanting to use the word spell, '…incantation.’

Brother Anselm lifted up the metal cage and placed the chest underneath. There was no way he could see of fastening the cage to the stone, but he proceeded as instructed. He unrolled the parchment. Freeing his mind from the prayer that he felt had been keeping him safe, he visualised a bright white light. Taking a deep breath, he started the incantation. The language was strange; an ancient tongue which at first felt otherworldly after the beauty of his everyday Latin but which became familiar and comforting as he read on.

He finished and stood back.

Nothing.